Everything that’s wrong is right again!

Or what Wikipedia shows about age-old fundraising wisdom

By Caoileann Appleby - Jan 11 2019

We’ve all heard “the exception proves the rule”, right?

Many people take this to mean that an exception verifies the rule.

It’s actually from “prove” in the sense of “test”. This might be more familiar to you from Great British Bakeoff’s bread week (Paul fans, raise your hands! Anyone…? No, thought not). Proving the dough tests whether it’s good enough to bake. So, an exception tests the rule to see if it’s really as robust as it seems.

Which brings me to Wikipedia and fundraising wisdom.

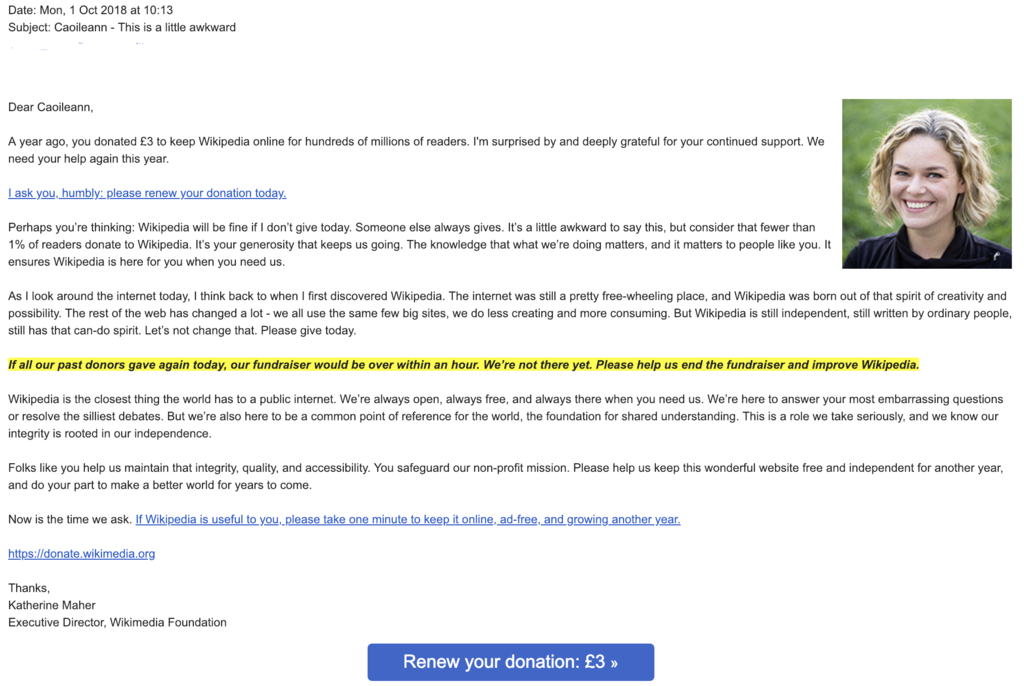

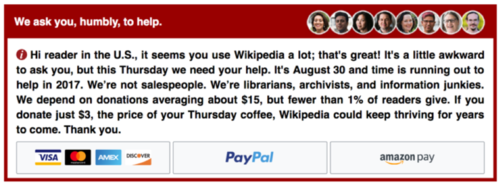

This year, they sent out their first fundraising emails on the 1st of October. Here’s the one I got:

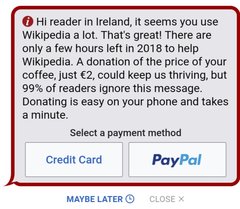

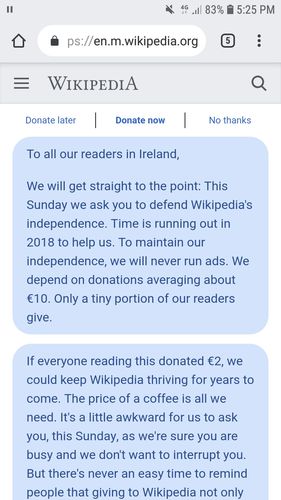

Followed by banner ads, and further emails, in numerous iterations until December.

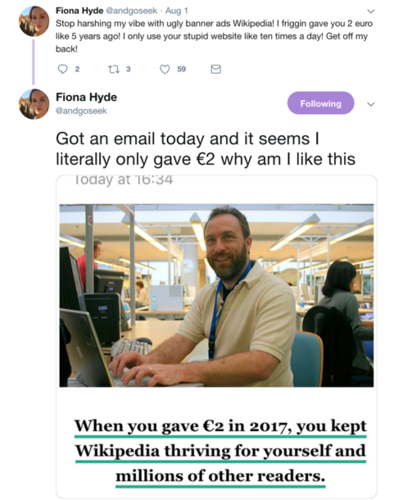

And while I’m always happy to be asked, and to see what different approaches charities take, as a professional fundraiser, I found them deeply irritating at first. I was reluctant to give again, because I hate rewarding bad fundraising with my money, even if I really like the organisation and the work they do.

And I wasn’t the only one who was annoyed.

They’re using techniques we would (nearly) always advise our clients to steer away from:

- Embarrassment and guilt: the emails and messages treat asking like it’s a bad thing, something to be gotten over with as quickly as possible – just look at that subject line “this is a little awkward”. Aren’t we proud to be fundraisers, proud of our organisations and what they do? Shouldn’t we be offering supporters the opportunity to give, not make them feel guilted into it?

- Negative social proofing: in case you’re not familiar with the term, ‘social proofing’ means using the idea of normalisation – framing an activity or idea by how common it is among your peers – to reinforce the desired action. For a general audience, positive social proofing is usually the way to go; negative social proofing – telling your target audience how uncommon the action is “fewer than 1% of readers donate” “99% of readers ignore this message” – is a surefire way to suppress response because it tells them not responding is normal and expected (it can, however, reap rewards for specific groups of highly-committed donors – more on that another time!).

- Anchoring low: they’re asking for the price of a coffee (or, in Italy, a metro ticket). This approach has been beautifully skewered by SNL and has arguably led to saturation issues in markets where it’s been used to the point that no charity ad is believable anymore (sure, you can buy a mosquito net for a few quid, but can you really solve child marriage that easily?). Yet here they are, asking for $3 or €2 or £2, not really telling us what it’ll be used for, and making the rest of us look bad by comparison.

However, they more I looked, the more I saw a lot that they’re doing “right”:

- They’re using what’s unique to them: not only their vast, vast volume to enable multi-variate testing (more on this in a bit) but also their values: independence, collectivism, freedom and accessibility. Values they bet enough of their users share.

- They’re testing (boy, are they testing): have I mentioned the testing? Copy, signatory, timing, visuals, asking to cover the cost of card fees, framing the ask: they’re testing a lot – and then they’re rolling out what works. You can read more details about that in their 2017-2018 fundraising report.

- They’re using previous giving history to shape the ask: making use of the commitment effect, asking a donor to match past donations increases response.

- They’re putting a human face on it: Wikipedia, as a resource, is pretty anonymous. Unless you’re actually involved in updating the site, as a general user it can seem like the site just gets updated by kindly elves or magic algorithms. So the Foundation shows us Katherine, and Jimmy, and puts a range of human faces on its banner ads, as well as bringing some personality to the copy (this example is from 2017):

Are there likely to be drawbacks to fundraising “don’t’s” they use? Sure.

Would this work for everyone? No.

Is it working for them? So far as I can tell: yes indeed. They’re raising more money year on year, and this year their average gift also increased.

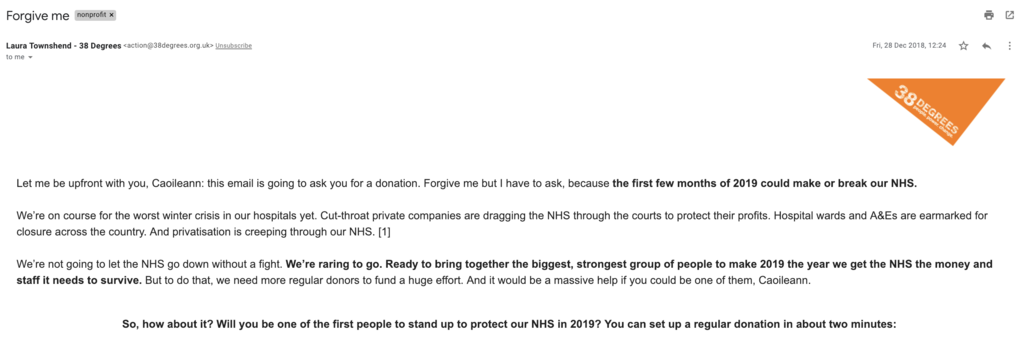

Imitation being the sincerest form of flattery, other organisations like 38 Degrees have also started to use similar techniques:

In this case, the exception has tested the rules of fundraising… and it seems they’re more like guidelines anyway.

Most of all, Wikipedia’s fundraising has reminded me, again, of Marketing 101 – a truth that the office décor of our friends at Bluefrog hammers home too – you are not your audience.

Contrary to the opinions of some – and as you probably have to reiterate to your board every so often – your personal taste has very little to do with whether a fundraising approach is effective or not. Your donors are the only ones who can tell you whether something will work, and they do that mostly through how they respond (not just how they say they’ll respond).

So, just because others veer away from a certain approach, it doesn’t mean it won’t work for you (just make sure you have very good reasons to think so, and enough testing volume to demonstrate it!).

And did I give again? Yes.

Caoileann Appleby @Qaoileann